Book Club Blogcheck out this page for thoughtful opinions, reflections, and analyses from book club participants

|

|

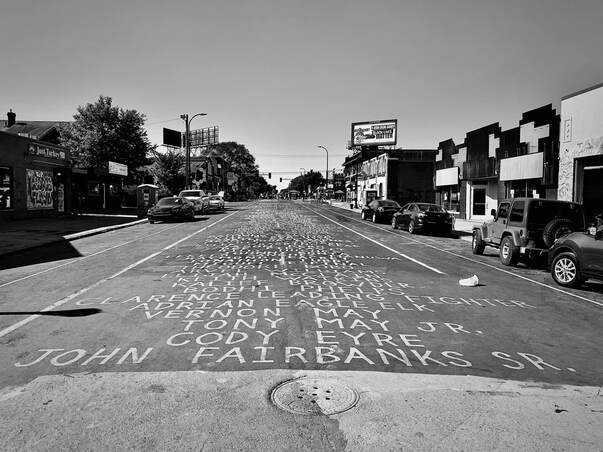

By: Arinjay Basak The Hate You Give, written by Angie Thomas, is a fictional novel about the life of Starr Carter, a 16 year old black girl living in the ghetto. Gangs, shootouts, drugs, prostitutes, and violence are all commonplace in the neighborhood, primarily inhabited by black residents. The general area being unsafe, she attends school an hour’s drive away, and is one of the few black students in a school with mainly a very rich, white demographic. The racial and financial contrast with her poor black suburbs leads her to create a front, in which she consciously doesn’t use slang, and carefully sounds out her syllables around her school in an attempt to not stand out in school. One night, leaving a party after hearing gunshots, Starr and her childhood friend Khalil are pulled over by a police officer, and Starr witnesses Khalil unjustly killed by the police brutality she had been warned about from her parents. Most of the kids in the hood were warned how to deal with cops: keep hands visible, don’t make sudden movements, and do what the cop says without talkback. Khalil, making a gesture to see if Starr was alright, moves his hand towards a hairbrush, which the cop mistakes for a gun. The only witness is Starr, but having had one of her close friends shot and killed in front of her once before, the PTSD and emotional stress takes a toll on her, causing her to have breakdowns and cry a lot more. After giving the honest story of how the incident went in an interview with the police, Starr realizes how skewed the media, law, and general public is in terms of finding the truth and justice in these cases. Finding out Khalil was a drug dealer, the media jumps on this, fabricating a story of the cop being afraid, and Khalil being hostile. This dehumanizes Khalil for everyone in the general public and even Starr herself, unable to believe he would take part in dealing something that took his mother away from him. Later, she learns he was forced to deal drugs to pay back the kingpin of a prominent gang to save the addicted mother who did nothing for him. Starr becomes critical of herself, and her white schoolmates who take the media at face value and sympathize with the cop. The Hate You Give is cleverly written so the reader is given a view of both the boonies and the affluent white families, and can see how differently they react to the media. The minorities that are subjected to unjust treatment by higher authorities and the law have been statistically shown to indicate racism from the officers that take part in these incidents. The media has been shown to dehumanize the victims of these cases, tending to go more in depth of how the police officer suffers from the shock of murdering someone in the moment. This happens because the police officer tends to have a stronger voice than the minority. For example, after Starr told her Uncle Carson the cop had his gun trained on Starr after killing Khalil till help came, Carson beat the officer up, which was highlighted in the news more than the fact Khalil was unarmed. The story is written from Starr’s point of view, so it’s bound to be biassed, but ideally this case comes down to 2 voices that should be in court. Here, the police officer fabricated a sob story to win over the media, and Starr didn’t have the opportunity to speak out. Of course, she might have lied about the incident, villainizing the cop to the media, but the voices deserve equal amounts of attention. These violent police brutality cases have a defendant, but need a prosecutor with a voice, or the protests won’t stop, and justice won’t come.

0 Comments

by Ethan Wang On February 12, 1942, nearly three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt issued Executive order 9066, which forced citizens with Japanese heritage to be held in incarceration camps, as they were perceived by the government as a threat to national security. The book Displacement by Kiku Hughes provides a view into the experiences of the Japanese American citizens as they lived in those camps by moving the main character from her life in the modern world to a life in an incarceration camp using an unexplained supernatural event. Through this supernatural premise, the author, Kiku Hughes, expresses the dehumanizing and unequal aspects of this executive order, as well as the activities and values among the Japanese Americans that helped them overcome challenges in the camps.

After the main character, Kiku, is transported to the time when all the Japanese citizens were being rounded up and transported to the incarceration camps. In this section, Hughes puts a lot of emphasis on how these people were being treated like prisoners of war. The busses that they were put on had their windows papered over to prevent the passengers from knowing where they were, presumably for the sake of preventing escape. The people in the camps were fed in a mess hall, with canned food, similar to the rations in a prison. Many people were taken from their families under the suspicion that they may be spies. Later in the story, these conditions are contrasted with the values of the United States, as the Japanese American children, including Kiku, learn about how the Constitution was written on the basis of freedom, security, and the right to property. Throughout the story, Hughes also stresses the importance of community in the camps, even among people who barely knew each other. For example, at the start of the story, Kiku, as well as many other people, worked with their roommates to fix up the barracks that they were housed in. Not only did this improve their housing, it also gave the Japanese Americans a sense that they could rely on each other. This bond was best highlighted when someone was shot by a security guard. Even people who did not know the person who was shot showed up for the funeral that the community held for him. Here, instead of being a weakness that gets them incarcerated, the Japanese Americans’ shared cultural heritage becomes an advantage, as it strengthens the bonds within the community. While the book Displacement does a great job portraying the experiences of Japanese Americans during their internment through a more personal lens, it fails to show the broader effects of this event on the Japanese Americans. For example, the book does not delve much into how many people lost their property as they were being incarcerated, and never got it back. Arguably, this is one of the more personal effects of internment, as Japanese Americans are forced to rebuild their lives from scratch after they were released. The book also does not show much of what happens to the people after they leave the internment camps. While there is a section about Kiku’s grandmother becoming a talented violinist, her grandmother’s experiences are not typical of someone exiting incarceration, since most of them did not have the educational opportunities given to Kiku’s grandmother by a nonprofit. While not explicitly stated, the book stresses the importance of keeping personal and detailed records of what happened in the past. It is necessary for people to remember details and feelings of the people who have gone through these events in order to prevent such things from happening again. The book Displacement provides a great personal view into the lives of Japanese Americans as they went through the effects of Executive order 9066, which differentiates itself from history books that often only include statistics and objective descriptions. By Sonia Qi Characters in books often have their names deliberately chosen to correspond to their personalities and destiny. Yet in real life, many people feel their names do not suit them or feel the need for a name that fits their new environment, so they go through the process to legally change it. Officially changing one’s name only requires a petition and a public hearing, but it is also easy enough to ask people to call you something else. However, is it really that simple?

Names are central to one’s identity. A name can act as an identifier for a person’s gender, age, and ethnicity. After being called by a name for years, that name is no longer a normal word, but instead something linked to personal stories and social relationships. In Homegoing, characters have different types of names and relationships with their names that are inextricably linked to their destiny. A surname is the family name inherited from one’s ancestors, and in Homegoing, it also represents family history, status, and responsibility. The white chief of the Cape Coast Castle, a fort used in slave trade, passes the last name of “Collins” on to his progeny. For Quey, inheriting the family name also means inheriting his father’s whiteness and the family business — slave trade. Quey must compromise for his family, blaming white people in order to feel a sense of kinship with his fellow Africans, reluctantly taking over his father’s work, and marrying the daughter of the Asante king for protection. Unlike his father, James refuses to follow the path his family chooses for him. He cannot feel at ease with the money and respect garnered to him by the slave trade. To escape the control and shameful work of his family, James abandons his name. He moves to a remote village with a brand new identity, so he can be his “own nation.” There he is given the name “Unlucky” because his crops never grow, and yet he feels he is fortunate to be named Unlucky. "The convicts working the mines were almost all like him. Black, once slave, once free, now slave again." — Yaa Gyasi, Homegoing Name is so essential to one’s identity that the lack of a name can signify the absence of identity or a universal identity. H, who is given a letter as a placeholder for a name, is held captive as a slave, convicted of an unfair charge, and eventually works as a miner. He is nameless, powerless, and has a life like many others. Having no unique identity, H is a member of the union. He stands in for the “freemen” that work like slaves, those who get thrown in jail for minor reasons, and those who work underground for years. He also represents those who die in dust explosions, those who suffer death for not finishing a task, those who die in rebellion against the boss, and those who are oppressed because of their color. Another character with a similar identity is Ness, short for goodness. Working in the cotton field for her entire life, she is killed by her owner after saving a girl from being beaten by the owner’s son. Like H, Ness embodies the anonymous slaves that work industriously, are cruelly tortured, and die quietly. She is one of them and all of them. They are insignificant while living and have nothing left after death. “‘Taking away your name is the first step’” — Yaa Gyasi, Homegoing A cultural name often represents a culture’s history. Changing an African cultural name to an English name, similar to the prohibition for the slaves to speak in their own language, is a step toward erasing the African culture and identities of individuals. Ness is stripped of her original name, Maame, and Akua is forcibly given the name Deborah; in this way, both are forced to undergo the process of assimilation. Beyond calling Deborah “sinner” or “heathen,” the white Missionary constantly refers to her race and connects it with the Christian belief that he wants to impose, attempting to turn her against her culture. In the example of Kojo, the only thing he has of his mother is his name. Kojo is still a baby when he leaves Ness, and he knows nothing about the history of his family or people. His African name is an essential part of his identity, and shortening his name to Joe is akin to cutting himself off from his heritage. The name Joe might make Kojo more American and perhaps even make his life in the U.S. easier, yet at the same time, he loses part of his African identity. “We don't know when our name came into being or how some distant ancestor acquired it. We don't understand our name at all, we don't know its history and yet we bear it with exalted fidelity, we merge with it, we like it, we are ridiculously proud of it as if we had thought it up ourselves in a moment of brilliant inspiration.” ― Milan Kundera Sometimes, people change their names voluntarily, which often signifies their transition to a new identity. Amani changes her name from Mary because she thinks its meaning of harmony suits her new identity as a singer. Despite the criticism of abandoning their original name, it is not uncommon for people to use a different name in a new country primarily due to pronunciation or spelling issues or potential discrimination based on their foreign name. Personally, adopting the name Sonia marked an important change in my life when I moved to the U.S.. In the beginning, Sonia felt very much like a normal word, given that Sonia was a random girl’s name my mother found online. I could just as easily have been named Emily, Claire, or Hannah. My Chinese name is different; Leheng was selected by my parents. Le is equivalent to the word “laugh”, and heng has the same pronunciation as “forever” and means a type of jade, an auspicious item in Chinese culture. Compared to the name I had used my entire life, I could barely feel any connection to Sonia. Nevertheless, I stuck with Sonia to avoid questions regarding the pronunciation of my name and not being even more different from all my classmates. I separated my life into two worlds and used my names as the key. In both worlds, there is a part of me that exists outside the perimeter and never gets seen. This two-world system operates so well that having my father calling me Sonia would be weird to me. As I live with this identity, and more and more people recognize me as Sonia, it almost feels as though I am using my experiences in America and emotions related to this identity to fill the name Sonia. This name becomes more special to me that I started to also identify myself as Sonia. By Alice Feng “I guess [the airport is] the only place I didn’t have to explain anything. Everyone was in-between.” — Eddie Huang, Fresh Off the Boat In Fresh Off the Boat, Eddie Huang writes about his life and hardships as an Asian American who feels neither fully “Asian” nor fully “American.” Wandering around the airport, he feels a relief that he doesn’t have to explain himself to anyone, whether that “anyone” be from Taiwan or Florida. Huang's struggle affects Asian Americans, as well as anyone growing up with two cultures. As an Asian American, I too find myself relating to some of his challenges. As an Asian American who loves so many aspects of Chinese culture from music to clothing to food to TV series. As an Asian American who lives in a community mostly made up of Asians - especially Chinese - people where everywhere I turn is some Chinese restaurant or grocery store or school. Even though my life differs greatly from Huang’s life, who grew up in a predominantly Caucasian and African American community and who loves hip-hop and basketball, I still find myself asking the question of “where do I fit in society?” Living between two cultures and his own personality forms the central conflict of Huang’s narrative. Early on, Huang is bullied for being Chinese, which might have made any child want to bury their Asian background. His schoolmates call him and his brothers “chinks” and various other slurs and announce that his Chinese food was “stinky,” an insult which I too have experienced. Many of his peers’ parents also display a lack of education about Asian culture, even using the outdated colonialist term “Oriental,” and ask where Eddie’s family was really “from.” With new forms of racism such as the Fox Eye trend, the scapegoating of Asians for the coronavirus, and the ever-pervasive Model Minority Myth, the situation has failed to improve since when Eddie was a child. Eddie himself also doesn’t feel like he is fully American. Despite being a citizen and born and raised in America, he talks about how he’ll never “hold an American flag, own a USA bumper sticker, or rock a Dream Team jersey that doesn’t say Barkley.” Eddie also says, “If they did try to see me as one of “them” it wasn’t in my true form; it was as a reformed, assimilated, apologetic version of myself that accepted the premise that my people were barbarians”Belonging for Huang comes at the cost of sacrificing and apologizing for his own identity and assimilating to the American culture. While assimilation rings false to Huang, he also fails to identify with the Asian community. When arguing with his father over his wish to become an ESPN sportscaster, he realizes, ““not only was I not white, to many people I wasn’t Asian either.”” Evidently, in Huang’s case, this is because he is a “loud-mouthed, brash, broken Asian who had no respect for authority in any form.” However, this feeling of not fitting in with the Asian community applies to many Asian Americans who may not be as loud-mouthed, brash, or outspoken as he is. I, for instance, wouldn’t consider myself as vocal or as blunt as Eddie (in fact I usually pass as a stereotypical “well-mannered” Chinese girl at first glance), yet there are still many ways I’m unable to fully assimilate with societies in Asia. My observations come from a mixture of my parents’ story of China, Chinese media, American media on China, and my first-hand experience of going to China and visiting both my older and younger relatives there. Of course, the most direct barrier between me and my family and friends in China is language; despite speaking mostly Chinese at home, I lack experience with modern Chinese slang and traditional idiom usage, pop culture references, and speed of speech. Photo obtained via: https://www.fabiaoqing.com/biaoqing/detail/id/572985.html Then, there are the deeper fundamental differences that even studying the culture and history cannot change because of how I have grown up in the United States. Chinese (and perhaps this can be generalized to Asian) people have a centuries long tradition of a preference for collectivism over individualism. Chinese families tend to promote the idea of being like everyone else and for putting family and society over oneself. America, on the other hand, tends to promote being unique and individualistic. This clash between collectivism and individualism has several implications. First, people in China are more likely than people in the United States to follow orders from the government which has no inherently positive or negative implication until we look at specific cases. For a more positive implication, we can look at the example of the Covid-19 pandemic. In China, the government ordered citizens to wear a mask and follow extremely strict contact tracing rules, and most people rigorously followed the rules. Now the pandemic has died down so much that large parties are once again happening in Wuhan with no drastically negative impact. In the United States, however, people will first debate about the implications of wearing a mask because the government ordered it. Perhaps they may reach the conclusion that wearing a mask limits their freedom, privacy, and comfort, and as a result, they end up not wearing one and spreading the coronavirus to others and maybe even dying themselves. It’s truly sad to regularly see examples on the news of someone infected with the coronavirus because they were not wearing PPE or were in an area with poor social distancing. For a more negative implication, we can look at the idea of discussion. In Chinese schools, discussion is, for the most part, not encouraged, and neither is talking in class or questioning teachers and authorities. On the other hand, many American schools encourage debates, round table discussion, asking questions, and the like. This discouragement of discussion in China extends to outside of the classroom where discussion of many topics such as homosexual relationships, time travel (as to not disrespect history), ghosts/monsters, and subversive behavior are highly suppressed. People also criticize the government and talk about “controversial” topics much less openly in China than in the United States partly out of fear of consequences, partly because of what has been instilled in them by tradition and society. Now again, the reason I went into such detail on these differences between China and the United States is to show how fundamentally different these two places are, and as a result, the reason why it’s difficult for someone growing up in the United States to fit in in China (or Asia), and vice versa. Of course Asian Americans need not fit in with either Asians or Americans; they have their own Asian American community. (Indeed, there never really is a need to fit in with any group, regardless of one’s background, but it may be more comforting to some to have a group of people who look like them, have the same interests as them, have grown up in the same situation as them, etc.) However, Huang makes the point that many Chinese Americans either resent their Chinese background or compete to be more “Chinese” (i.e. who has more love for Chinese food, more points on the SAT, more instruments they have mastered, more AP courses under their belt), both of which make it difficult to form a united community. At the end of the day though, Huang and most children of American immigrants are proud of their ethnicity and wouldn’t choose to live as any other ethnicity. As Eddie says, “What they didn’t understand is that after you have the money and degrees, you can’t buy your identity back. I wasn’t worried about degrees, but I cared about my roots.” An identity is something that everyone values. Just like the airport is a world of in-between, so is living as an Asian American (or any other mix of cultures or races). As an Asian American, you grow up in between two cultures, each with its own language, food, pop culture, history, and people, and you are entitled to both cultures. You’re able to communicate with “twice” the number of people and can act almost as an ambassador between the two cultures, as you most likely have some understanding of both. By being an Asian American, you create your own unique identity, and this identity really demonstrates a redefinition of culture in the 21st century, a time of social activism and change -- especially by the younger generations. Asian Americans are also realizing that they can boldly define their own Asian American identity without necessarily undermining their Asian and American cultures. They are learning both that there is no shame in embracing their Asian heritage while also not being afraid to take on the American culture, a culture completely untouched by their ancestors. Today, as more and more Asians immigrate to the United States and the Asian American population, one of the fast-growing racial or ethnic groups in the United States, rises in numbers, the Asian American identity takes a shape clearer than ever before. This is Eddie Huang, author of Fresh Off the Boat. Image courtesy of ABC/Image Group LA via Flickr, creative commons license. Although Huang faces a variety of difficulties stemming from his Asian American identity, the story really is about him creating a place for himself in this world, something that many readers can personally relate to while reading his memoir.

about the author: Alice loves reading mystery, historical fiction, and dystopian stories as well as stories inspired by current events and issues that reveal a life different from that of the reader’s yet still takes place in the same world or maybe even same country. Other hobbies of Alice’s include figure skating, watching Chinese drama, and designing, creating, and selling unique handmade bracelets. By: Claire Yang Fresh Off the Boat is an autobiography by Eddie Huang, who narrates his life from being a bullied and abused child to becoming the owner of a restaurant in New York.

Oh, and he’s Chinese-American. And so am I. Here is my experience reading this book, encapsulated as a blog post: First off, so many of Huang’s references to hip hop and pop culture soar right over my Gen-Z head. Much of the slang he uses is also completely unfamiliar to me. In short, I more than once felt as if I was reading Shakespeare again in ninth grade, except this text was far grittier and louder. This is to be expected. After all, there is a generational divide between the author and me, as well as a complete difference in where we have lived and our overall life experiences. I cannot fully grasp his struggles and passions, nor the pop culture ingrained into him. But there is one thing about his story that resonates with me: his Asian American identity and how he grapples and comes to terms with it. From the Mandarin sprinkled throughout the text to references to various Chinese dishes, Huang explores and highlights this facet of his life in his autobiography. His ethnicity behaves like a double-edged sword, building up part of his identity as an individual while also leaving him vulnerable to stereotypes that would erase his very individuality. He connects and interacts with Chinese-Taiwanese culture, even setting up his restaurant to be “a voice for Asian Americans.” I particularly want to focus on two aspects of being Asian American that Huang mentions:

2) In the book, Huang detailedly describes two separate trips to Taiwan, once as a child with his family and later as an adult attending college. In both occasions, he reconnects with and explores his Taiwanese background. On the first trip, he becomes awed and “want[s] to know more about Taiwan and what it mean[s] to be Taiwanese.” On the second trip, he “look[s] around and s[ees] [him]self everywhere he [goes].” He continues to poignantly describe: “Pieces of me scattered all over the country like I had lived, died, burned, and been spread throughout the country in a past life.” Huang recognizes the struggle in maintaining both halves of an Asian American identity and the process of rejecting and reaching for certain aspects of each half. I know that many Asian Americans have trouble connecting with their Asian backgrounds. For me, one thing I can relate with Huang is that poignant moment where you discover you want to learn more about your own cultural background. Unfortunately, this moment comes hand-in-hand with the understanding that there might always be a disconnect between you and being “Asian.” Could I say that being Asian American is both very interesting yet feels very typical? I might be able to summarize my reaction towards Huang’s book in a blog post, but I’m far from finished with my thoughts on being Asian American. about the author: Claire really enjoys getting lost in books and stories. She mainly reads fantasy and fiction novels, but she currently is reading more books/memoirs about different perspectives in America. She also enjoys drawing and listening to music. by Diwakar Basak Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give revolves around the central theme of racial inequality and what one did to address that theme in her neighborhood. The main character is Starr Carter, a black teenager, who lives in a racially and economically segregated neighborhood in the Southern United States. She has to swap between her two lives: one in the poor, black suburbs, the other in the wealthy, primarily white school which she attends. Starr feels conflicted between her two lives, and this conflict prevents Starr from speaking up when white cops unjustly kill her black friend, Khalil in her neighborhood. One of the cops shot Khalil, assuming that he was part of a gang they were trying to arrest, when the young teenager pulled out what he thought to be a pistol. The police hide any evidence of the manner of Khalil’s death from the public. Afterwards, they call an ambulance and leave the scene. Only Starr, who was with Khalil at the time of death, knows what unfolded. She cannot bear Khalil’s death in the weeks after facing grief, sadness, anger, and hate. Starr feels afraid of speaking out because she thinks she has failed to live up to Maverick’s belief in black power. However, she eventually comes out of her shell when she realizes she must speak up in order to save the community she is part of and herself. Starr’s actions in The Hate U Give mirror the actions that the Black Lives Matter organization took to advocate for non-violent civil disobedience in protest against incidents of police brutality and all racially motivated violence against black people. To analyze the story, we attempt to answer a few questions relating to the plot. The first question is why the police did not want to reveal to the public the manner of Khalil’s death. The answer is that the police were fearful of how the public, especially African Americans and other black activists, would react to the fact that one of their police had shot and killed a black teenager, unjustly. In the past and modern day, we see examples of civil unrest all over the globe in the form of riots breaking out whenever an abuse of power occurs. An abuse of power occurs when a civil government misuses their power. In The Hate U Give, the police abuse their power in two ways: first, they kill Khalil unjustly, second, they throw tear gas into the peaceful crowd of protesters, who are chanting Khalil’s name. Both of these are examples of police brutality, a fairly common, yet serious issue in modern day United States. Statistics show that police brutality affects minorities, people of color, at much higher rates than the white majority. Many believe that the reason for this is the discrimination that minorities face on account of white supremacy, the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and therefore should be dominant over them. It is an issue that plagues us in modern-day society. Because of it, black people are “dehumanized” and are the target of excessive violence by cops. A recent account of this is the Ferguson police shooting where the cops fatally shot a black man named Michael Brown. If racism has damaging, lasting consequences, (can result in the unjust death of a marginalized demographic) people of color will fear the police more and will more likely flee/resist in a police confrontation. This will likely lead to more deaths as abuse of power will deem violence necessary to ease the situation, leading to a proliferation of the problem. Although one might argue that public safety tries to promote utilitarianism and is trained to handle violent situations, the abuse of power by representatives of public safety in our society remains unchecked and excused by the illusion of promoting additional training. In The Hate U Give, when the cop killed Khalil, his intentions may have been good - to promote the safety and well-being of the public - but his racist beliefs (moral judgement) may have clouded the way for reason and truth. The problem now that needs to be addressed is what must be changed. Is it how these cops are trained to handle situations like this? Or is it the underlying racist beliefs of cops? In the training regiment of cops, they have been trained to react appropriately in situations of danger. But for what cause? Do they let their personal beliefs/fears get in the way of logic and reasoning? This is obviously expected by any human being when confronted in fear, but that instinct can be trained and developed. For example, in the military, soldiers go through VR sessions in which they undergo battle scenes to reduce their fear instinct to prepare them for real battles, so that they are resistant to PTSD. The second issue we need to focus on is how we can eliminate racism from affecting a cop’s mindset. To do that, we need to find a way to eliminate racist remarks from our conversations. We need public protest if we want to focus on responding to events of injustice. Public protest is necessary because it is an outlet for a fraction of the public to voice their fears and opinions, which thereby allows the issue to be transformed into a larger one, one that the larger public must confront. When the issue appears on the national headline, perchance, most people will be forced to examine the issue deeply and contemplate for themselves. Is there anything we can do to inspire people to change their views/beliefs? What do you think the members of the Book Club can do to combat racist remarks, pacifist convictions, and preconceived notions towards members of the Black community? Clearly, we need to do something to fight off racism as it has already become a really big issue in our country. As demonstrated in The Hate U Give, racist views can lead to unintentional violence by the police in the community. These violent scenes only lead to more violence that further devastate the community creating more strife and protest, essentially destabilizing a nation.

about the author: Diwakar enjoys reading mystery, sci-fi, and fantasy in his free time, but also likes to read fiction stories based upon real events and experiences relating to a variety of topics. Aside from reading, Diwakar likes to sing Indian classical songs, code, and play chess for fun. about the editor: Angela is an avid reader of mostly fantasy, dystopia, and sci-fi, but she is branching out to more non-fiction/realistic fiction novels to learn more about current issues and stories of different life experiences. Outside of reading, she enjoys coding, piano, and watercoloring. by Brian Xu Cristina Henriquez’s The Book of Unknown Americans is pieced together through a series of vignettes, detailing the lives of over a dozen immigrants in a Delaware apartment complex. The variety of perspectives this novel encompasses are key to emphasizing a core message: each person has an “unknown” story, wonderfully distinct from any other’s. Each immigrant carries a passionate motive for coming to the United States, and each has also faced innumerable setbacks ranging from finding employment to enduring racial discrimination. The children of these immigrants carry equally important stories, bridging the culture embedded in their ancestry with the American customs they’ve grown up absorbing. What is especially unique about the collection of rich characters within the novel is the complexity of their identities — though all of them can be placed under the umbrella of “immigrants” in the United States, the cast is diverse in gender, nationality, age, ability, and interests. It’s clear that racial tensions play a large role in many immigrant experiences in America, but Henriquez mirrors racial stereotypes and challenges in an unexpected way: through Maribel’s challenges facing judgment based on her disability. Henriquez embeds a common thread through numerous types of misunderstanding and stereotyping: communication barriers, and ultimately, a lack of true listening. When Maribel’s family moves to the United States, they face a literal communication barrier, grappling with basic English phrases while seeking out those who can communicate in Spanish. Alma gets lost after riding a bus several stops past her destination, and is trapped in a panicked frenzy by her inability to communicate and ask for directions. Later on, she goes to a local police station to report Garrett for harassing Maribel, but is spurned — eventually, Garrett and his father are ultimately responsible for the death of Maribel’s father, Arturo. While Maribel doesn’t face such obvious challenges due to her mental disability, Henriquez still highlights how she is overlooked by those around her. Most of Maribel’s acquaintances, and even her parents, often start conversations with her by asking how she feels, a question she “hates” for its implication that something is wrong. Each time a stranger is introduced to Maribel, they walk on eggshells around her disability and view her with pity. Only after Mayor invests time listening and getting to know Maribel does she feel connected to another person — ”I feel like you’re the only person who… sees… me,” she tells Mayor. Yet, there is so much unique potential hidden among the misunderstood. Before moving to America, Arturo owned a construction business in Mexico, but American outsiders would likely view him as just another mushroom farm worker. Rafael Toro turned his life around from drinking and fighting to instead save up money and marry Celia, and his stubborn pride in supporting his family on his own is just a glimpse into his larger background. While Maribel has suffered a severe brain injury, she still displays incredible intelligence and is always listening, recording details she overhears in her notebook. While the novel ends following the tragic death of Arturo, the ending carries an optimistic tone — through the injustice the Rivera’s face, they have built a true community. Though nothing can reverse Arturo’s fate, all of Rivera’s neighbors as well as many acquaintances and coworkers chip in to help bring Arturo’s body to Mexico, where he can rest peacefully in the presence of his family. In the Riveras’ final moments in America, Alma sees Maribel through a new lens — ”Suddenly, out of nowhere, there she was…. Not exactly the girl she was before the accident… but my Maribel, brave and impetuous and kind.” Beneath the layers of tragedy engulfing the Rivera’s, the family has become more visible: Arturo is recognized as a kind individual who navigated uncharted territory with extreme optimism, Alma is able to move past the burden of her guilt for Maribel’s accident, and Maribel is finally viewed for her individuality rather than her disability. Though there are still countless unfinished stories throughout the novel, Henriquez presents a slice of life into communities that rarely receive the spotlight of mainstream media. She shows that through shared understanding and efforts to bridge diverse groups of people, we can view the “unknown” stories of those around us, allowing us to overcome trauma together and appreciate the beauty of different backgrounds. about the writer & editor:

about the author: Brian loves to read realistic and historical fiction to gain more awareness of other lifestyles and perspectives. He finds it rewarding to read the viewpoints of those he doesn't get to interact with from day to day. When not reading, Brian enjoys journalism, programming and playing the piano. by Angela Jia and Brian Xu “We start with stars in our eyes We start believing that we belong” — Dear Evan Hansen What is the American dream? Our wildest hopes and greatest goals achieved? Equal opportunity no matter the background nor past experiences? A clean slate to start anew with infinite possibilities? It sounds too good to be true, and for countless immigrants who come to America in hopes of a better life, in hopes of the American dream, maybe it is only just a dream. “But every sun doesn’t rise And no one tells you where you went wrong” — Dear Evan Hansen The immigrants from The Book of Unknown Americans have come to America in hopes of a better life for themselves or their loved ones: Arturo and Alma to provide a better education for their daughter, Rafael and Celia to escape their war-torn home country, Benny to escape poverty, Gustavo to provide for his children, Fito to become a pro boxer, and Nelia to become a theater superstar. In doing so, they were forced to abandon all they knew and build up a life in a foreign place among foreign people. But I keep wondering, was it worth it? Alma doesn’t dare let herself think whether coming to America was worth it because her family has sacrificed so much to be here, and Celia yearns to return to her homeland. Fito gave up on his pro boxer dreams, becoming an apartment manager instead. Nelia couldn’t seize any opportunities to become a superstar; instead, she started her own theater in Delaware. Although Fito and Nelia are satisfied with their life now, I somehow feel that they are only settling, rather than living the elevated life they dreamed for themselves. They are happy, but are they truly more happy than they would have been without coming to America? “When you’re falling in a forest and there’s nobody around. Do you ever really crash, or even make a sound?” — Dear Evan Hansen None of these immigrants had planned to settle down in Delaware, trying to make the most of what life has thrown at them. But no matter how strong their resolve to find some semblance of success in America, factors outside their control continue to beat them down. Arturo lost his job after switching his shift to see his daughter off on her first day of school, losing his visa and his family’s legal status along with it. Rafael lost his job at the restaurant after fifteen years due to the declining American economy. Alma found no support or help from the police when she tried to report Garrett’s assault on Maribel. In fact, the police asked if she was “a pretty girl,” insinuating that such offenses were normal, and stated that it was Alma’s job to protect her, not blame the police. None of these immigrants received any external help when they needed it, as if America turned its back on them when it couldn’t get anything in exchange. The gears of this country keep grinding on, neglecting the immigrants who have chosen this place to be their home. “Have you ever felt like you could disappear? Like you could fall, and no one would hear? Well, let that lonely feeling wash away Maybe there’s a reason to believe you’ll be okay.” — Dear Evan Hansen Like Evan Hansen from Dear Evan Hansen, the characters from The Book of Unknown Americans yearn to be seen, to be heard, and accepted as part of a community. But the pre-existing communities choose to ignore them and fence them out. As a result, although individually, every character suffers from personal hardships and disillusionment, they have created their own community of misfits, finding each other when all others have turned their backs against them. Fito’s apartment building is “an island for all of us washed-ashore refugees. A safe harbor.” When Alma attempts to reach across the sea outside her harbor, she is met with unresponsive waves, and she feels “simultaneously conspicuous and invisible, like an oddity whom everyone notices but chooses to ignore.” But within her community, their shared language is the common thread that binds them together. Although we never really see them exchange stories about their hometowns and pasts, their shared understanding of what it’s like in the present, living as a Latin American immigrant in Delaware, allows them to connect. As Alma puts it, “there was a certain comfort that came with hearing someone speak Spanish, to understand and to be understood, to not have to wonder what I was missing.” These immigrants may have left behind their various home countries, and they may not have yet achieved their American dreams, but they’ve found a home amongst each other in America. about the writer & editor:

Angela (writer) is an avid reader of mostly fantasy, dystopia, and sci-fi, but she is branching out to more non-fiction/realistic fiction novels to learn more about current issues and stories of different life experiences. Outside of reading, she enjoys coding, piano, and watercoloring. Brian (editor) loves to read realistic and historical fiction to gain more awareness of other lifestyles and perspectives. He finds it rewarding to read the viewpoints of those he doesn't get to interact with from day to day. When not reading, Brian enjoys journalism, programming and playing the piano. by Asolia Zharmenova & Katie SimpsonIn her TED talk “The Danger of a Single Story”, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie made a powerful statement about the power of stories She said: “I've always felt that it is impossible to engage properly with a place or a person without engaging with all of the stories of that place and that person. The consequence of the single story is this: It robs people of dignity. It makes our recognition of our equal humanity difficult. It emphasizes how we are different rather than how we are similar. “ Adichie’s speech emphasized the power and necessity to elevate stories of individuals and communities in writing and rhetoric. Personally, I was moved by her words to consider ways in which I often fail to provide space and listen to the stories of those around me; because more often than not, I fill in the gaps in my knowledge with stereotypes so as to avoid facing a simple reality of being human. As we began reading The Book of Unknown Americans last week, many of us expressed the difficulty of keeping up with the multiple perspectives of different characters that are introduced with each chapter. Perhaps, the author Cristina Henriquez chose to place the tone of each perspective in the first person, so as readers we only collect a portion of each character’s story that they have chosen to disclose and recognize the individuality within each story as well as the commonality between stories. It seems that the characters are united by their setting, circumstances, and new cultural identity as they retell stories of their immigration or navigate a new way of life as newly resettled individuals. Though many of the narrators share the experience of immigration, each person's perspective in narrative is filled with individuality. For example, the generational divide between the two main narrators, Alma and Mayor, shapes their experience of migration and of life in America. Where Mayor experiences the “in-between” identity of a young immigrant, Alma experiences the profound displacement of leaving the only home you’ve ever known. Yet both know what it is to be seen as an outsider by the majority culture. Within every apartment is a different collection of intergenerational stories, combined to form a larger community. Now, returning to Adichie’s talk (which I encourage everyone to listen to if you haven't already), what are ways in which we might begin to respect the stories (specifically immigrants), so as not to “deprive them of their dignity”? I think one of the best ways is listening to the voices of those immigrants who came in the former generations. The history of immigration in the United States is far more complex than the “melting pot” narrative. Nevertheless, it is a history worth our study. Policies such as family separation and the attendant news coverage degrades the dignity and right of the migrants themselves as they are reduced to the status of either a parasite or a helpless victim rather than the complex human beings they are. Although it feels as though we can’t do much to help those who are suffering because of their national identity, by keeping ourselves informed we begin to do justice to their full humanity NPR’s This American Life received a Pulitzer Prize for their coverage on the lives of people at the Mexican/US border. Thanks to the efforts of these reporters, we hear first-person accounts of the unique experiences of individual migrants rather than reducing them to anonymous figures. As listeners, although we do not see them, we hear their voices. We hear their stories. And perhaps, we begin to realize not just how our stories are different from those of the migrants, but how they are the same in the human desire for well-being and flourishing. That is the simple reality. With that foundation in mind, and thanks to the work of novelists like Henriquez and journalists like Molly O’Toole and Emily Green, we might become less prone to assuming a single story for all. As we read the first-person accounts of Alma and Mayor as well as other residents in that little community somewhere in rural Delaware, might we consider the interplay of their stories as uniquely individual and fundamentally human. about the contributors:Asolia studied piano performance at a small liberal arts college on the outskirts of Boston, MA. She teaches piano and tutors English and writing on the side. In the future, she hopes to travel more and learn French. |

Archives |